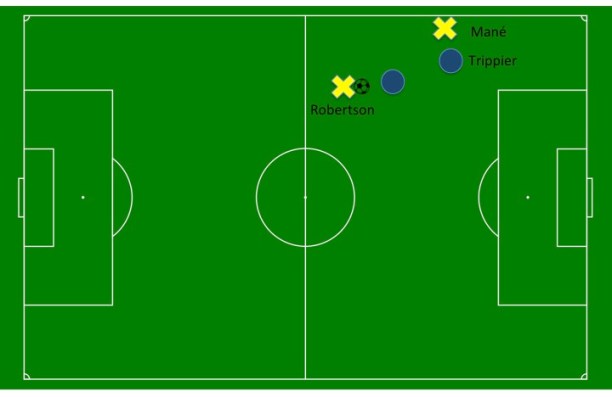

The dilemma facing defenders is whether to hold the line or get goal side of your opponent. When an attacker gets goal side of the defender, it is self-evident to suggest that the defender should have been goal side, particularly if the resulting outcome is a goal. Given the frequency with which this happens it is worth understanding the circumstances that contribute to these defensive failings.

With zonal defending, there are a number of factors going through the mind of a defender when the opposition are attacking. These could range from holding one’s position or whether to go towards the player on the ball. If one goes towards the ball, the concern is who is going to fill the gap that is left?

It is important to maintain the defensive line, particularly around the penalty box, because if just one of the line drop back towards the goal it could impact the offside trap. And yet, dropping back towards the goal is likely to be the movement you are asking the defender to do when you want them to be goal side.

The decision to be goal side inevitably leads to abandoning the defensive line. Is this a group decision or an individual one? At what stage in the defending process should this occur? If the defensive line is being abandoned and the criticism is that a certain defender should have been marking a particular attacker, the goal scorer, what should the other defenders be doing?

Presumably, they should also be marking attackers as, before the ball comes in say from a cross, who knows where it is going to arrive? This begs the question of who is supposed to be marking each one of the main protagonists? There has to be a coordinated effort so as not to leave one person out. Invariably, there is one attacker in or around the box who is completely unmarked and the ball falls to them. Defenders are in the vicinity and may or may not have seen this player as a potential threat but nobody has assumed responsibility for the marking of this player. As the ball arrives it is too late to do anything about it.

Going man-to-man

A good way for the defence to solve this problem is to match-up in a man-to-man style with the opposing attackers. But when do you do this? Who’s going to organise it? If one person has been left unmarked, that would suggest the organiser is not doing their job properly. Is there an organiser?

There needs to be an organiser so that each defender is allotted someone to mark on the basis of proximity but also in the knowledge that every attacker is accounted for. As we have seen, you cannot afford to miss one out.

The abandoning of the defensive line, the straight line of defenders that is the cornerstone of every football team’s defensive strategy as though it were stated in international law, is a big deal. The whole defensive structure of the team is based around this and we’re not sure if it is an individual or a team decision to make this call. One thing is clear. If the call is not made, the defenders will not be goal side.

Which matters more?

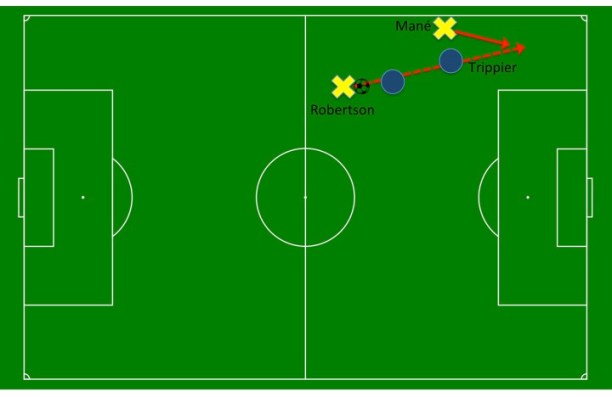

Don’t forget, the moment a centre forward stands in the straight defensive line, alongside one of the opposing centre-backs, none of these defenders will be goal side on this particular opponent. In order to be, they have to step back a few steps so the attacking player is in front of them rather than alongside. But in stepping back, the same forward can also step forward to reinstate the position alongside the last man in defence.

The defensive line either has to keep retreating towards its own goal or it maintains its line, high or low line, and in doing so these players are not goal side. So, the simple statement of saying that a particular defender should have been goal side is a bit more complicated than it first seems.

The basic principle of any defensive system is to prevent goals being conceded. A basic principle of individual defensive technique is to be goal side on one’s opponent. If we take the scenario where a goal is actually conceded and the post-mortem that prevails identify how this situation could have been avoided and specifically the role of various defenders. In those situations where the goal scorer is clearly not being marked, questions will inevitably arise. Of course, there is an expectation that the goal scorer should have been marked. In other words, the defender should have been goal side.

Marking space or players

This implies that a defender should, at least, have been matched up against this attacking player. The matching-up process is akin to a man-to-man defensive set up. Ultimately, in any defensive system, defending will come down to one defender matching up against one attacker. Thus, we should not be fazed by the concept of man-to-man marking. It ought to be regarded as a natural part of any defensive system.

Zonal marking

Even with zonal marking, in the final analysis, the opponent on the ball has to be marked. The nature of zonal marking, as opposed to man-to-man marking, means that the identity of the defender who one should be matching up against is not always clear. It will come down to an allocation process whereby someone in the defensive unit, probably a centre-back, will take charge of allocating defensive responsibility to all fellow defenders.

This is where the ambiguity begins. The allocation of marking responsibility will take a certain amount of time. If this process hasn’t been completed before, say a cross comes into the penalty box there will not be sufficient time to make this allocation while the ball is in flight. Defenders need to know, in advance, who they are responsible for.

With man-to-man, whilst you will start out in a zonal shape, the process of allocating marking responsibility starts much earlier and so by the time the play gets around one’s own box, the identity of who each defender is responsible for has been established.

Fulham 1 Tottenham 2 Premier League 20thJanuary 2019

Fernando Llorente, replacement for Harry Kane, opened the scoring for Fulham with an own goal!

Spurs goals:

The first was a delivery by Christian Eriksen from just outside the right corner area of the box to Deli Ali with a free header at the far post. There was no pressure on the ball so Eriksen was able to look up and pick out his pass. No marking of Ali either. The full back could have tucked in and possibly provide some resistance, but didn’t. Why? Is it a lack of concentration or is it to do with the zonal shape?

The pundits, Jamie Redknapp and Graeme Souness claim that the defender needs to be goal side. Yes, but as we have seen being goal side would require them to abandon the defensive line. The confusion for the full back is, knowing when to make this decision. The decision is also, effectively, taking responsibility for the marking of a particular opponent.

With hindsight it is all so obvious. But, if this one defender does take responsibility for this one offensive player (Ali), should the other defenders also be taking responsibility for other attacking players?

There should be a team strategy to ensure that all the main attacking threats are accounted for. This entails not just one player but several players taking responsibility for the marking of opponents. The implication of this is that the defensive line, the zonal defensive line, is abandoned in favour of matching up with opponents in a man-to-man defensive organisation.

In situations where crosses are being played into the box, it seems reasonable to ask what is the point of a defensive line? It is the same point as before: to keep the opponents on side. But now they are just one touch away from scoring and the defender is not in a good position to do anything about it.

It is quite plain to see, from the closed body position of the defenders as opposed to an opened-out one, that the backline is still intent on upholding the defensive line, a feature that is completely consistent with the zonal shape mentality. When a cross comes in, generally the defenders are looking at the ball with possibly the occasional glance over the shoulder to see who is behind.

Unfortunately, this is not the best technique for defending against an opponent. The defender needs to be opened out in such a way to be able to see both the ball and the player they are marking. To do this, one has to move back a few yards, adopting a goal side position, in order to utilise one’s peripheral vision. This way they are able to anticipate the movement of the forward and this means they can then contest the forward’s movement. In layman’s terms, get in their way.

In the case of Ali’s goal, notwithstanding the limitation of defensive technique, the decision to drop and abandon the defensive line was taken too late, if at all.

In reality, the individual defender doesn’t even know the identity of the player they should be marking as the cross comes in. It all happens so quickly. These are the details that can so easily be overlooked when post-match analysis ensues.

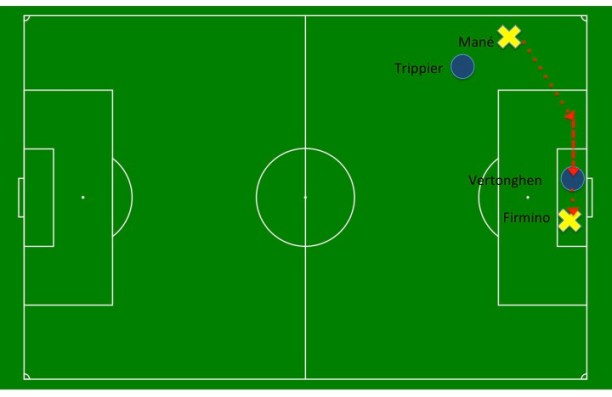

The second goal, right at the death, was a carbon copy of the first as far as the defensive frailties are concerned. Only this time the cross came in from the other side of the pitch and Harry Winks ghosted in to head home from about two metres. The left full back for Fulham on this occasion was criticised for not being goal side. No pressure on the cross coming in. The goal scorer was not being marked.

Another example. The day before:

Wolves 4 Leicester 3 Premier League 19thJanuary 2019

Wolves opened the scoring inside four minutes when Jota arriving at the back post was hungrier than Danny Simpson, the Leicester right back and was able to just get his foot ahead of the defender to stab home. The same defensive errors prevail.

This is a recurring theme and the basis of this dilemma is the zonal shape.